Carbon Markets: From Problem to Solution

The goal of reducing carbon in the atmosphere in order to mitigate the negative effects of climate change is not new. The first commitments were agreed to by nation states under the U.N.’s Kyoto protocol in 1997. Ratification of the 2015 Paris Agreement by all but six member countries demonstrated a global commitment to tackling the problem. Unfortunately, enacting solutions that bring results and can scale have failed both in speed and effectiveness, leading to great uncertainty to the extent of the commitment by nation states and to the solutions that have been brought forward to date. It is our opinion that, much like waste, carbon emissions are pollutants, negative externalities that need to be priced and compensated for based on the amount of carbon generated by each individual or business. While mandatory carbon “credit” markets in the cap-and-trade[44] model have not yet been established in every country, the emergence of voluntary carbon “offset” markets around the world offer great promise for a solution that could be far more decentralized, transparent and effective. Both the regulated and unregulated markets (see status on development) have their own challenges, but ultimately both are failing to scale due to poorly aligned incentive structures and lack of trust in the quality of the carbon credits/offsets being offered, and the carbon reduction results that they promise to bring.

Let’s take a brief look at each of these models. The mandatory carbon credit markets are a centralized solution established and regulated by nation states or nation unions, such as the EU, utilizing Emissions Trading Systems (ETS) to establish and manage a cap and trade market. Companies are allocated a number of carbon emitting allowances, “a Cap,” based on their emissions and the allowances are reduced over time based on the industry in which they operate. Emitting more carbon than is allowed forces the company to buy credits from the market. Emitting less carbon allows it to sell or trade its allowances in exchange for cash. The incentive structure is designed to help companies understand the forecasted cost of carbon and produce positive financial results to the company by investing in cleaner solutions that cost the company less than what would be paid as a carbon penalty. Money is transferred from companies that are not reducing their carbon emissions fast enough to companies that are reducing their carbon emissions more quickly, and any extra cash injected into the system flows to the regulator.

The second model is the voluntary carbon offset market where individuals and companies engage with each other directly and agree to transfer value between each other in the form of purchased offsets. Projects can be of any type and carbon offsets can be certified by a third party or not. The unit of trade is the equivalent of one (1) ton of carbon emissions, also known as CO2e, in the same manner as the mandatory carbon markets. Other greenhouse gasses (GHG), such as methane, can also be expressed as CO2 equivalents. Companies often purchase both carbon credits and offsets to comply with cap and trade requirements, to meet investor ESG goals and to adhere to customer expectations (branding and marketing, mostly.) While the voluntary carbon markets exceeded US$1 billion in value in 2021[45] and are expected to grow to US$10-25 billion by 2030 and US$90-480 billion by 2050 (calculated using year 2000 prices) the mandatory, or ETS market, were at US$261 billion in 2020, with the EU’s ETS (Emissions Trading System) representing 90% of the total value[46]. The much larger mandatory/involuntary market demonstrates that some form of regulation and the use of market forces is needed to induce companies to address their negative externalities (i.e. pollution.) While there are examples of very successful carbon emission reductions programs (e.g. Germany’s emissions have decreased by 40.8% compared to 1990 beating its original target[47]). Unfortunately, the actual success in reducing carbon emissions on a macro level is often questioned (only 3.8% reduction between 2008 and 2016 in total for the EU[48]) and more importantly, if it is enough to meet the goals of limiting global warming to 1.5ºC. According to the UN’s IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[49]), much more needs to be done, and much faster, because an estimated 3.3 - 3.6 billion people are already at risk.

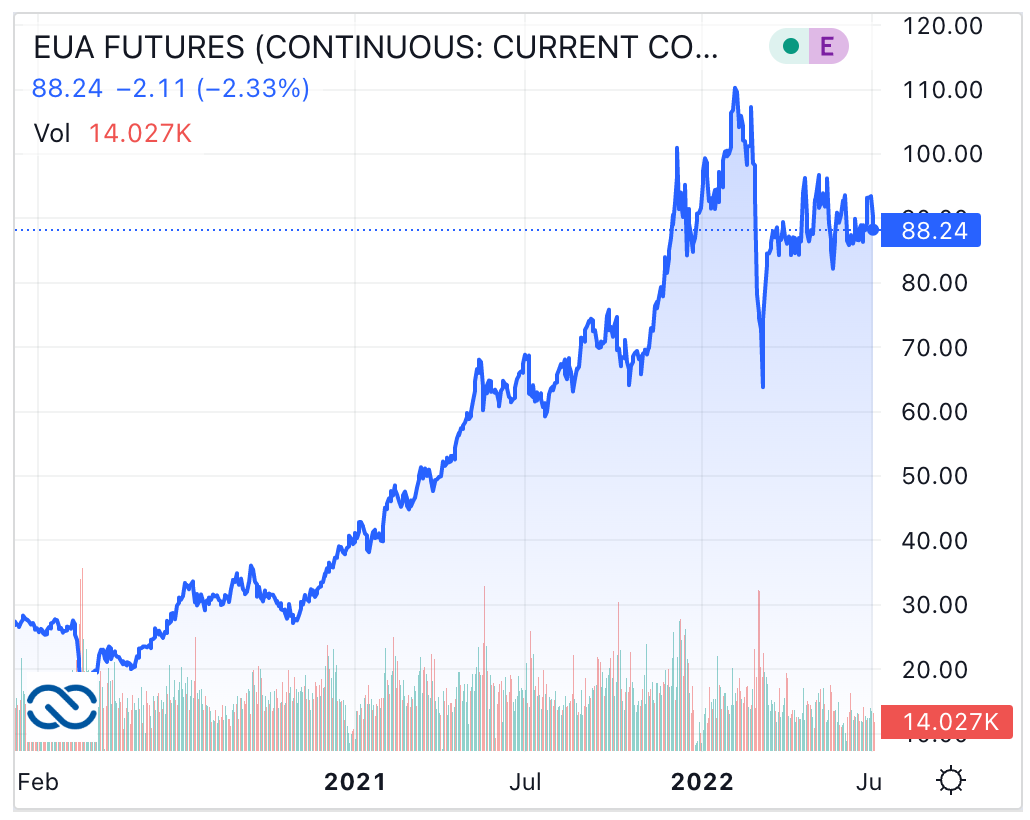

The reasons for limited success are many. First and foremost, not every major economy has a mandatory ETS market to price carbon, with notable abstainers including the United States, Brazil, India and Indonesia. Second, there is great volatility in carbon prices and the prices themselves are still too low to encourage a shift away from emitting carbon. In other words, it is cheaper to buy inexpensive carbon credits, or pay fines, than to actually invest in “decarbonizing” existing operations. The IMF recommends prices above US$75/ton while a Reuters poll of economists suggests it needs to be at least US$100/ton[50]. Since the beginning of 2022, the price of carbon has increased significantly in the EU ETS to a trading range between US$70-110 per ton, showing promise[51].

It should be noted that the price per ton of carbon in the California mandatory Carbon Credit Market trades at roughly ⅓ the value of the European Carbon Credit Market and that the price per ton of carbon in the voluntary markets can be significantly lower, even below US$5 per ton. Third, not every industry is required to offset carbon emissions. The focus for EU’s ETS is on power stations, energy-intensive industries (e.g. oil refineries, steelworks, and producers of iron, aluminum, cement, paper, and glass) and civil aviation[52]. Fourth, carbon accounting is complex both at the national and project level. Countries cannot agree on targets. Negotiations with regard to exceptions, in particular for developing countries, are complex and hard to settle, often leading to states abandoning the effort altogether (e.g. the United States left the Kyoto protocol in 2001.) Cross-border projects, such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) with trading of certified emissions reduction (CER) credits, have thus far had little impact. The cross-nation carbon trading proposal, such as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, attempts to promote collaboration between countries by letting countries trade credits between each other, but also surrenders control to governments with varying interests and perhaps quality standards in meeting their emissions targets, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Trust gaps are leading to unilateral decisions such as the Carbon Border Tax being implemented by the EU on imports[53]. Carbon accounting at the project level is extremely difficult, even with the support of “comprehensive global standardized frameworks to measure and manage greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions[54]” provided by the Greenhouse Gasses Protocol. Businesses can have very different emissions levels for similar operations, and variation can occur due to location, temperature, humidity and other factors. Performance can vary as equipment ages or if maintenance is not performed correctly. Real-time measurement and verification is rarely available. In some cases not all greenhouse gasses (GHGs) are measured and some GHGs are harder to measure than others. Some projects offer carbon reduction, avoidance and removal benefits into the future (e.g. reforestation, improved forest management, wetland restoration) while others are backed by realized environmental performance. Fraud and corruption with project certification is always a concern. The E.U. in 2012 stopped allowing member states to buy credits fearing projects (typically outside the EU and in particular from Russia and Ukraine) were not as successful in reducing emissions as they claimed to be. “A 2015 report found that an estimated 80% of projects under the Kyoto carbon trading scheme were of low environmental quality and that the system had actually increased emissions by roughly 600 million metric tons.[55]” The lack of trust in carbon accounting has led to the rise of third-party verification and certification solutions with varying degrees of requirements, solutions from the likes of Gold Standard and Verra which are playing an ever-increasing role in the voluntary carbon markets, in particular to help companies purchase real offsets that are actually producing climate-positive results. But, while certification institutions are part of the solution they are not THE solution. Certification is slow (often taking 3-5 years), extremely expensive (often costing US$250-500,000) and typically limited to only the highest of polluting projects. Long response times and project-by-project certification presents a significant scaling challenge in its current form. The certifying institutions often hold on to their own stock of credits which are not made available on a public registry. This leads to the risk of carbon credit double counting as projects can be listed on more than one registry and sold to multiple parties with no way for a company to verify if the credit it purchased is unique. For projects that are delivering results into the future, often there is no follow up to ensure that the environmental performance was actually delivered (Were the trees actually planted? Are they still there and growing?) Who determines what credits are valid is also a major concern. Verra pulled its credits from the Toucan Protocol (a Web3 solution for tokenizing carbon credits on a public blockchain), stating that the quality of the credits and the environmental value behind them weren’t properly being accounted for. Verra claimed instead that they would be working with bank-led initiatives, like Carbonplace, rather than pure crypto projects.[56] Finally, and probably most significantly, carbon has an intrinsic challenge in that it is intangible. You can’t see it. In the eyes of the average individual and business owner, carbon emissions equivalency estimations are often seen as a random number inserted onto a spreadsheet.

We at the Carrot Foundation believe, for the reasons presented above, that while the carbon markets will evolve over time, they will not scale in the short term and produce the carbon reduction results desired by the majority of the parties. We believe we can help dramatically scale carbon reduction by applying Web3 solutions to the circular economy, helping to reduce carbon emissions through recycling and composting operations and establish a carbon and material waste offset exchange on a public blockchain. Note, as presented earlier, 49% of greenhouse gasses, measured on a systems-based approach, comes from the provisioning of food and products to consumers. Transitioning from a linear economy to a circular economy eliminates long carbon-intensive supply chains, reduces raw material extraction, eliminates methane emissions in landfills and produces the compost that improves carbon capture from the atmosphere, thus closing the loop on the carbon cycle. The carbon reduction benefits of recycling and composting are well documented and science-based. Resources for measuring CO2e reduction (methane and carbon) are readily available, including those developed by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)[57] under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)[58], the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) greenhouse gasses measurement from the WARM model[59], and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol[60], to name a few. The opportunity is to leverage these frameworks and apply them to the recycling and carbon markets in a manner that can reduce greenhouse gasses and pollution in general. Practically every single human being, organization and community across the globe generates physical waste (post-industrial and/or post-consumer) every single day. Physical waste is tangible, measurable, trackable and immense in volume, so reducing waste, both visible and greenhouse gasses, can be accomplished because we can confirm its recycling with new technology that brings a high degree of confidence, corroborated through proof-of-provenance, using chain of custody and material mass verification. These can be recorded in traditional logistical operations demonstrating proof-of-physical-work and we can issue, or mint, tokenized recycling and carbon credits that will likely become the highest quality carbon credits anywhere.

Homologated recyclers, along with independent validators and auditors from the Carrot Foundation can confirm environmental performance of credits and provide businesses with the assurance they need to enter the voluntary market en masse, followed soon after by the involuntary markets as well. Ownership of “burned” tokens, or “sunk” credits, will be listed on a public blockchain and available for further verification by regulators, investors and consumers without risk of double counting. A global, public leaderboard of stored carbon waste offsets by businesses and individuals will bring unprecedented transparency to the regulatory, capital and consumer markets, expanding the access and adoption of ESG and, eventually, affecting consumer behavior at the point of sale and thus minimizing waste production. This is how we address undesired consequences, by incorporating them into the cost of doing business while offering simple and trustworthy paths for businesses to pay their fair share and help fund the transition to a global economy that manages its resources far more efficiently.

What is most promising, however, is the role that decentralization can play in reducing waste, waste-based pollution and climate change. Action on climate change and management of waste and its resulting pollution is, currently, exclusively in the hands of governments and large corporations. Most people don’t have the financial resources to purchase an electric vehicle or install solar panels on their roof. But every person, business and community around the world can sort their waste at little or no additional cost. This simple act of sorting transforms every individual and organization into an environmental worker who can contribute to a less polluted, more efficient and job-creating world, lowering the costs and losses that come with waste. The opportunity of creating a community that is both local and global, and that is self-governed through a DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization) is far more powerful than anything that has been built thus far. Informed consumers, united and working together, can lead to important positive changes to the global economy. Imagine when you can look at your shopping cart and know the recycled material content in each product and its package, the carbon footprint of the product and if the product is recyclable in your area; all data provided by third parties, not the manufacturers. Post-consumption, imagine having real-time data on the success of your sorting, recycling and composting efforts; with the environmental results presented to you. Imagine when you can earn tokens as rewards for the contribution you make in sorting, hauling, processing and recycling waste, demonstrating your positive role in your local and global communities.

Imagine when the $CARROT tokens you receive give you ownership and voting rights in an ecosystem with which you are part, enabling you to participate in its future, vote on executive leadership, help with project development and determine the redistribution rewards that each stakeholder should receive in the global recycling economy.

We believe we can help put the responsibility of building a better world in the hands of the people. Not everyone has to participate, but enough can to make a significant difference and together we can solve one of the most complex problems in the world. This is our vision for the future.

44. Investopedia: Cap and Trade definition

45. S&P Global, Commodity Insights report: COP26: Voluntary carbon market value tops $1bil in 2021: Ecosystem Marketplace

46. CarbonCredits.com site: Overall size of carbon offset markets and Global Compliance Market

47. Clean Energy Wire: Germany’s greenhouse gas emissions and energy transition targets report

48. PNAS - The European Emissions Trading System reduced CO2 emissions despite low prices report

49. United Nations - IPCC: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability report

50. Reuters Poll: Carbon needs to cost at least $100/tonne now to reach net zero by 2050

51. CarbonCredits.com site: European Carbon Credit Market and California Carbon Credit Market

52. Clean Energy Wire, factsheet: Understanding the European Union’s Emissions Trading Systems

53. European Commission: Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, adopted proposal

54. Greenhouse Gas Protocol, site: About page

55. TIME article - How an Obscure Part of the Paris Climate Agreement Could Cut Twice as Many Carbon Emissios - Or Become a ‘Massive Loophole’ for Polluters referencing a Stockholm Environment Institute report titled Russia, Ukraine dodgy carbon offsets cost the climate - study.

56. Time - article The Crypto Industry Was On Its Way to Changing the Carbon-Credit Market, Until It Hit a Major Roadblock

57. UNFCCC - AMS-III.F Avoidance of methane emissions through composting - Version 12.0

58. Clean Development Mechanism: methodologies

59. US EPA: Basic Information about the Waste Reduction Model (WARM)

60. Greenhouse Gas Protocol: Protocol for the quantification of greenhouse gas emissions from waste management activities presentation

Last updated